connecticut statistics

rates of imprisonment increasing

THE NUMBERS

For perspective, currently, there are approximately 11,000+ individuals incarcerated in the state of Connecticut. That said, Connecticut’s population is the lowest it’s been in 27 years as of April 13th, 2020. As of July 25th, 2020 there are 1,385 fewer people behind bars than on March 1st, 2020, the beginning of the pandemic.

On April 29th, 2020, the prison population fell to 11,062, the lowest since 1993. Arrests are the main feeder into the Correctional institutions. Naturally, this creates an influx of people, mainly formerly incarcerated, back into society with no real plan of action or outlets. Once you dig into the numbers a little more, you will see that the release of black inmates increased by 52% in these 2 periods, the release of Hispanics increased by 40% during the same time, and the release of Whites increased by 5%.

As you can see there was a big increase in discretionary release between March 2019 and March 2020 and it was larger for blacks and Hispanics than the total inmate population.

Admissions fell, releases increased and court operations were impacted. The use of social distancing was believed to be a factor in the closures of small businesses. Where do we go from here? The ability to innovate is more important than ever!

INFO: CT Dept. of Corrections

Connecticut Profile

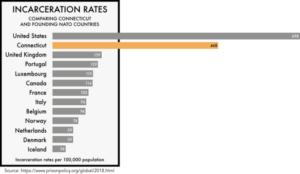

Connecticut has an incarceration rate of 468 per 100,000 people (including prisons, jails, immigration detention, and juvenile justice facilities), meaning that it locks up a higher percentage of its people than many wealthy democracies do. Read on to learn more about who is incarcerated in Connecticut and why.

Are you looking for information on what jails and prisons in Connecticut are doing to stop COVID-19? See our regularly-updated coronavirus response page.

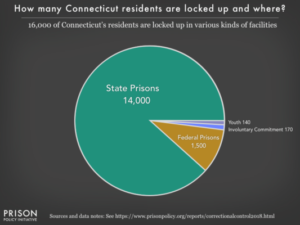

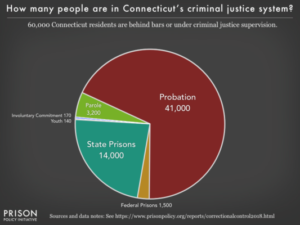

16,000 people from Connecticut are behind bars

(Graph: Alexi Jones, December 2018)

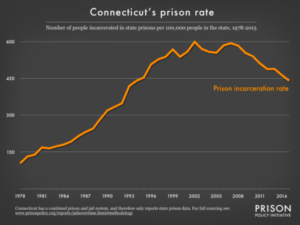

This graph is a part of Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state. For more research and graphs about Connecticut, see our Connecticut state profile. Rates of imprisonment have grown dramatically in the last 40 years

(Graph: Joshua Aiken, May 2017)

This graph is a part of the Prison Policy Initiative report, Era of Mass Expansion: Why State Officials Should Fight Jail Growth.

- total numbers rather than rates.

- Women’s prisons: Incarceration Rates | Total Population

- Men’s prisons: Incarceration Rates | Total Population

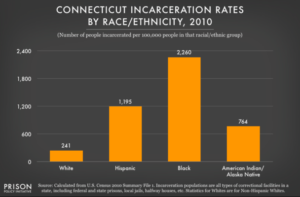

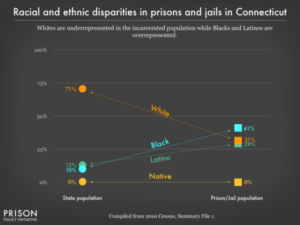

In the U.S., incarceration extends beyond prisons and local jails to include other systems of confinement. The U.S. and state incarceration rates in this graph include people held by these other parts of the justice system, so they may be slightly higher than the commonly reported incarceration rates that only include prisons and jails. Details on the data are available in States of Incarceration: The Global Context. We also have a version of this graph focusing on the incarceration of women. People of color are overrepresented in prisons and jails

Data Source: U.S. Census 2010, Summary File 1. (Graph: Leah Sakala, May 2014)

This graph is a part of Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity, a Prison Policy Initiative briefing.

(Graph: Peter Wagner and Joshua Aiken, December 2016)

This graph is a part of 50 state incarceration profiles.

See also our detailed graphs about Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks in Connecticut prisons.

Connecticut’s criminal justice system is more than just its prisons

(Graph: Alexi Jones, December 2018)

This graph is a part of Correctional Control 2018: Incarceration and supervision by state. For more research and graphs about Connecticut, see our Connecticut state profile.

Other articles about Connecticut

• We graded every state’s response to the coronavirus in prisons and jails. Connecticut got an F+

• How much do incarcerated people in Connecticut earn for their work in prison?

• Connecticut prisons charge a $3 copay to incarcerated people, putting health at risk

• We graded the parole release systems of all 50 states – Connecticut gets an F

• Connecticut state prisons still charge more than most other states for telephone calls

• Who’s helping the 1,281 women released from Connecticut correctional facilities each year?

• Our letter to the Hartford Courant: Prison Expansion Won’t Aid Local Economy

Sentencing enhancement zones in Connecticut

• Reaching too far: How Connecticut’s large sentencing enhancement zones miss the mark

• Misconceptions about sentencing enhancement zones persist in the Connecticut Legislature

• New animation illustrates the real size of Connecticut Sentencing Enhancement Zones

Prison-based gerrymandering in Connecticut

• Ending prison gerrymandering in Connecticut campaign and resource page

• Connecticut organizations call on the legislature to end prison gerrymandering

• A new fact sheet about prison gerrymandering in Connecticut

• Imported “Constituents”: Incarcerated People And Political Clout In Connecticut

• Importing Constituents: Incarcerated People and Political Clout in Connecticut

PRISON POLICY INITIATIVE UPDATES for February 3, 2021 Showing how mass incarceration harms communities and our national welfare

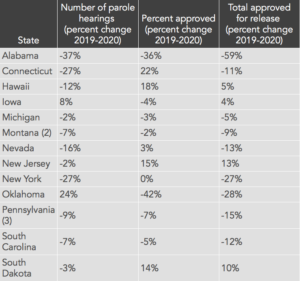

The Prison Policy Initiative takes accuracy very seriously, but in our rush to make a newsletter version of our research today, we jumbled some of the data about parole hearings in the below table. A corrected version is below. (And as always, a more detailed and visual version is on our website.) We apologize for the error.

Parole boards approved fewer releases in 2020 than in 2019, despite the raging pandemic

Instead of releasing more people to the safety of their homes, parole boards in many states held fewer hearings and granted fewer approvals during the ongoing, deadly pandemic.

by Tiana Herring

Prisons have had 10 months to take measures to reduce their populations and save lives amidst the ongoing pandemic. Yet our comparison of 13 states’ parole grant rates from 2019 and 2020 reveals that many have failed to utilize parole as a mechanism for releasing more people to the safety of their homes.

In over half of the states we studied — Alabama, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina — between 2019 and 2020, there was either no change or a decrease in parole grant rates (that is, the percentage of parole hearings that resulted in approvals).

Granting parole to more people should be an obvious decarceration tool for correctional systems, during both the pandemic and more ordinary times. Since parole is a preexisting system, it can be used to reduce prison populations without requiring any new laws, executive orders, or commutations. And since anyone going before the parole board has already completed their court-ordered minimum sentences, it would make sense for boards to operate with a presumption of release.1

But only 34 states even offer discretionary parole, and those that do are generally not set up to help people earn release. Parole boards often choose to deny the majority of those who appear before them.

Except for Oklahoma and Iowa, parole boards held fewer hearings in 2020 than in 2019, meaning fewer people had opportunities to be granted parole. This may be in part due to boards being slow or unwilling to adapt to using technology during the pandemic, and instead of postponing hearings for months. Due to the combined factors of fewer hearings and failures to increase grant rates, only four of the 13 states — Hawaii, Iowa, New Jersey, and South Dakota — actually approved more people for parole in 2020 than in 2019.

Denying people parole during a pandemic only serves to further the spread of the virus both inside and outside of prisons. As the number of cases and deaths in prisons due to COVID-19 continues to rise, parole boards still have the opportunity to help slow the spread of the virus by releasing more people in 2021.

Footnotes

1. It’s important to note that people released on parole are not truly free and complete the remainder of their maximum sentences under community supervision. There are many problems with community supervision, including that it sets people up to fail with strict conditions and intense surveillance. But in the context of the pandemic where mitigation efforts like social distancing are virtually impossible inside of prisons, it is generally safer for people to be released into a flawed community supervision system than to remain behind bars.

2. We calculated Montana’s parole numbers by the 2019 and 2020 calendar years, using the official list of decisions for each month published by the Montana Board of Pardons and Parole. However, the Montana Department of Corrections’ 2021 biennial report notes the total number of parole hearings, number of approvals, and number of denials, broken down by fiscal year. Here, the DOC reports a much higher grant rate, which we were unable to replicate using the monthly data from the Board of Pardons and Parole.

3. Pennsylvania Act 115 (2019) reduced the number of people eligible for parole hearings by creating the presumptive release for some people serving sentences of two years or less. The Act likely contributed to the drop in parole hearings and approvals in Pennsylvania in 2020.

How much have COVID-19 releases changed prison and jail populations?

Sharing four new data visualizations and two data tables, we summarize the changes in prison and jail populations in 2020. We conclude that very little of the drop in prison populations were actually due to COVID-19 releases and that states failed to use every tool they had to depopulate prisons and jails during a deadly pandemic.

See the graphics and read our analysis.

Decarceration – and support on the outside – is the answer, not therapy behind bars

We discuss a new report from Professor Susan Sered, which finds little evidence supporting the idea that building new prisons for women will lead to better outcomes, even with gender-responsive and trauma-informed programming.

Read our discussion of the new report.

Decarceration—and support on the outside—is the answer, not therapy behind bars

A new report finds little evidence supporting the idea that building new prisons for women will lead to better outcomes, even with gender-responsive and trauma-informed programming.

by Prison Policy Initiative, February 3, 2021

In January, as the United States government prepared to execute Lisa Montgomery, news stories described the horrific sexual and physical abuse Montgomery experienced throughout her childhood and adult life. These accounts are shocking — but devastatingly, not so unusual. Studies suggest that more than half of women in state prisons survived physical and/or sexual abuse before their incarceration.

Prisons themselves are fundamentally in opposition to the goals of supportive programming.

A prison is a horrible place for people struggling with symptoms of past trauma, as well as those with histories of mental illness and substance abuse. Well-meaning policymakers sometimes suggest building “kinder, gentler” prisons that offer needed counseling — and indeed, one such project has recently been proposed for convicted women in Massachusetts — but in practice, prisons themselves are fundamentally in opposition to the goals of supportive programming.

Professor Susan Sered, along with Erica Taft and Cherry Russell, has just published an extensive review of the research on the outcomes of existing, prison-based therapeutic treatments — particularly for women. They conclude that the value gained from prison-based trauma, mental health, and substance abuse interventions is far outweighed by the harms caused by incarceration. Instead, they argue, alternatives outside of prisons that provide trauma-informed support, alongside practical interventions such as housing assistance and health care, are far more beneficial than anything that can be offered in a prison setting.

Prison is inherently traumatizing

Incarceration itself is retraumatizing and damaging to mental health. “Prisons are full of trauma-triggers,” Sered and her co-authors write, “such as unexpected noises, sounds of distress from other people, barked orders, pat-downs, strip searches, and looming threats of punishment for breaking any one of myriad rules.” Incarcerated women often experience new traumas and indignities, including the loss of their children and families, their bodily privacy, and their freedom of movement, time, and personal space. Meanwhile, “prison conditions including noise, crowding, lack of privacy, substandard diet, insufficient fresh air, harassment and ongoing threats of violence and punishment are further associated with negative health impacts.”

Treatment can retraumatize clients when authoritative or coercive methods are used.

Even the most well-designed and decorated prison is still a prison, and inherently unconducive to trauma-informed therapeutic programs, where participants are encouraged to acknowledge their trauma and engage in practices that promote recovery and wellness. “Treatment can retraumatize clients when authoritative or coercive methods are used,” the authors explain. “Ideally, trauma-informed treatment should take place in a warm, welcoming, and uncrowded space that provides room for a ‘time-out’ option. These conditions are difficult to meet in a prison context.”

There is an insufficient study of the long-term benefits of prison-based therapy

Prison-based therapy programs show some benefits: The review notes that “a meta-analysis of studies published between 2000 and 2013 identified reduced recidivism rates for women who participated in gender-informed correctional interventions.”

However, the authors also point out that there has been little study of long-term benefits. This is in part due to logistical challenges: It can be difficult to locate and follow up with study participants post-release. Summarizing a study from 2020, they write: “While mental health services in prison can partially protect some women from some of the strains of being in prison, there is little evidence that these services are of many benefits after they leave prison.” They further note that they “could not identify any studies that evaluate program impact in terms of variables such as post-incarceration employment, health or family reunification.”

Incarcerated women are often urged to self-improve, while men are more likely to get real-world jobs and educational support.

What’s more, while gender-sensitive prison-based programs may benefit participants in some ways in the short term (a welcome effect in a prison setting), troublingly, at least one cited study suggests that these programs may over-emphasize “individual pathology.” Along the same lines, another study finds that staff often urge incarcerated women to see the error of their ways and “self-improve.” Incarcerated men, meanwhile, are more likely to report more practical support, such as staff helping them gain real-world jobs and educational skills.

Similar problems plague drug treatment in prisons

Prisons are also inherently difficult places to participate in substance abuse treatment. “The prison environment itself creates added stress which may lead some people to seek psychotropic substances—both prescribed and illicit,” the authors write, noting that many prisons also resist evidence-driven, medication-assisted substance abuse treatment.

To study the results of compulsory drug treatment, the authors point to a 2018 Canadian review of court-mandated drug programs, which found that “forced treatment did not improve outcomes for substance use. Instead, findings showed higher levels of mental duress, homelessness, relapse and overdose among adults after discharge from mandated treatment.” They also quote a 2016 meta-analysis of compulsory drug treatments, which concluded: “Evidence does not, on the whole, suggest improved outcomes related to compulsory treatment approaches, with some studies suggesting potential harms.”

Recommendations:

Unfortunately, while there are numerous models for community-based alternatives to incarceration, they generally suffer from a similar lack of rigorous, long-term research as prison-based therapies. Therefore, the authors cannot recommend specific programs.

Community-based alternatives can be cost-effective and keep women out of prison in the first place.

They do note, however, that studies suggest successful prison alternatives would “set realistic expectations for participants, avoid using threats of punishment to obtain compliance, and refrain from sending participants to prison because of drug use.” Research into the reentry needs of formerly incarcerated women shows that justice-involved women often benefit from support in the areas of economic marginalization and poverty, housing, trauma, and family reunification.

This fits with the recommendations of Sered and her coauthors: They suggest that alternatives-to-prison programs for women provide practical support, including housing assistance, family reunification, help establishing community relationships, health care and substance abuse support, and restorative justice programs. When executed correctly, the authors argue that community-based alternatives could be cost-effective and help keep women out of prison in the first place.

Partners resources and Services

If you are interested in reaching our Latino market, or you just want to add your products/services to our website for a competitive monthly fee, this is your opportunity. Contact us.

G.E.M.S., reserves the right to review services and products submitted to ensure that it coincides with our mission.

Link only

Perfect for companies that need to promote their website.

$9.99

- Link and Click

- Company Logo

business boom

Our best value!

Perfect for businesses that are innovative and creative and have state-of-the-art products to promote. Purchase today!

$24.99

- Link and Click

- Company Logo

- Resource Informational (event, promotion, flyer)

Elite Unlimited

Take your business to the next level by providing visible products that will be engaging to your clients.

$34.99

- Link and Click

- Company Logo

- Business Card

- Resource Informational

- Featured Video (30 sec.)